The following abstracts were reviewed by the organising committee and accepted into Furry Studies 2025. Abstracts follow the table.

All times are local to Tacoma, Washington (Pacific Daylight Time, UTC -7).

Workshop: October 30, 2025

If you’re new to the furry community, this workshop is for you!

Separate registration required. This workshop is not streamed.

3pm – 5pm, Xavier 201

Supporting Furry Clients: Affirming practice within queer and trans communities

Hazel Ali Zaman, PhD

Jacob A Sandoval, PhD, LMFT

Conference: October 31, 2025

| Time | Session |

|---|---|

| 08:00-09:00 | Registration Coffee Break |

| 09:00- 09:15 | Zoom session starts Welcome to Furry Studies 2025 By Hazel Ali Zaman-Gonzalez (Sibyl), Conference Chair Video |

| 09:15-10:15 | Opening Keynote Rod O’Riley Video Q&A |

| 10:15-10:30 | Coffee Break |

| 10:30-12:00 | Session 1 In Media Roars: Furry across media artefacts Moderator: Xavier Ho (Spaxe) Video (introduction) Q&A (for all presenters in this session) |

| Furry Stickers and Semiotic Landscapes: Linguistic Anthropological sketches Eduardo Lactaoen Abstract | Video Furry Music: An analysis of composers, producers and convention performances João Araújo Abstract | Video Enter the Anthropomorphocene: Furry video games as a lens to examine human and non-human experience in the post-Anthropocene Reuben Mount Abstract | Video An Anthology Without an Editor: The impact of Funny Animals (1972) on the furry art market and its valuation Ian Gray Abstract | Video | |

| 12:00-1:00p | Lunch Break |

| 1:00-2:00 | Artist Panel 1 Virtual Artist Lecture Series I.V. Nuss, Lane Lincecum, and Mark Zubrovich Moderators: Brett Hanover (Auryn) and Tommy Bruce (Atty) Video Q&A (for all presenters in this session) |

| 2:00-3:30 | Session 2 Furry Planet: Furry in a global context Moderator: Tom Geller (Jack Newhorse) Video (introduction) Q&A (for all presenters in this session) |

| Eurofurence: The tail of the travelling convention Tim Stoddard Abstract | Video Fursonas Under Surveillance: Furry identity, resistance, and digital expression in Iran Shahriar Khonsari Abstract (presentation cancelled) Keep Furkeley Weird: A case study in queering the face of academia online Furries @ Berkeley Abstract | Video Furry and Anthropomorphizing Animals as a Response to a Hostile World Furscience Abstract | Video | |

| 3:30-3:45 | Coffee Break |

| 3:45-5:15 | Session 3 Non-Human?: Furry identities and (trans)species perspectives Moderator: Hazel Ali Zaman-Gonzalez (Sibyl) Video (introduction) Q&A (for all presenters in this session) |

| Brushing Up Against Species: Transgender feminist worldbuilding through fursuit practices Alec Esther Abstract | Video Trans-Species Panic: The furry slope of anti-trans legislation Alexander Rudenshiold & Caro Mooney Abstract | Video Sparklefurs: Virtual avatars, physical embodiment, and intergenerational histories in the furry fandom Belle Walston Abstract | Video Chasing Our Tails: (Trans)species critique and coalitional politics Juniper Clark Abstract | Video | |

| 5:15-5:45 | Snack Break |

| 5:45-7:15 | Artist Panel 2 State of the Art: A furry artist panel discussion Glopossum, outsidewolves, Zephyr Kim, and Julia Moderators: Brett Hanover (Auryn) and Tommy Bruce (Atty) Video |

| 7:15-7:30 | Closing Remarks By Hazel Ali Zaman-Gonzalez (Sibyl), Local Chair Video |

| Zoom session concludes Informal Social Dinner |

Session details

Furry Stickers and Semiotic Landscapes: Linguistic Anthropological Sketches

Eduardo Salinas Lactaoen, Department of Linguistics, University of Alberta

This presentation builds on previous work by the author examining practices of sticker gift giving and exchange within the furry fandom I draw primarily from Mauss’ analysis of gifting in The Gift as, focusing on the extension of personhood into the gift itself as the reason for reciprocity in gift exchanges. Presently, I focus on another aspect of furry sticker cultural practices: sticker distribution, both in inter-personal interaction and sticker bombing. Using autoethnographic examples, ethnography at furry conventions, and interviews with community members, I explore actual practices of exchanging, gifting, and posting furry stickers, focusing on those that depict one’s fursona. Pulling on the linguistic anthropological concept of linguistic and semiotic landscapes, I consider how sticker distribution practices serve to create a sense of furry ownership of the public space, both personal and communal. I also keep with Mauss’ idea that gifting and sacrifice are implicated in all aspects of a society’s cultural practices, and look at how the creation of said semiotic landscapes through sticker distribution is tied up with different sociocultural aspects of the furry fandom, including relationships between the furry milieu, furry institutions, and wider society; norms of furry socialization and friend-making; and the regulation of outward displays of sexuality and eroticism. I conclude with a more general discussion of how linguistic anthropological methods and theories can be fruitfully applied to gain a better understanding of how furry identity and social norms are constructed in actual practice.

Furry Music: An analysis of composers, producers and convention performances

João Araújo, Centre for Music Studies (CESEM), NOVA University Lisbon

The importance of visual art to the furry fandom has been well documented and is accepted by its members, recognized as an important medium for self and community-expression and an accepted professional and economic activity. While its definition is still debated, furry music is recognized inside the community, but it is rarely studied today. This presentation aims to introduce a contemporary mapping of the musical production of this community and its transformations in recent decades, as well as to begin a discussion on the definition of this music scene and its place inside this fandom, both online and in community conventions. On the production side, data was collected that allows us to analyze the musical genre distribution of this group’s creations. Regarding distribution and categorization, we can analyze the recognition of furry music as a distinct genre or scene among categorization websites, the existing playlists of furry music and the relative inclusion of music made by furries in these playlists and the methods that furries use to share and sell their creations. Finally, we can discuss the consumption of this music and the importance of the creator’s affiliation with the community to this consumption. As an exploratory, introductory study on this subject, definite conclusions are hard to reach, this presentation serving partially as a stepping stone into further understanding of this fandom’s artistic environment and is one piece of an ongoing investigation.

Enter the Anthropomorphocene: Furry video games as a lens to examine human and non-human experience in the post-Anthropocene

Reuben Mount, Birmingham City University

Post-apocalyptic fictions tend to focus on the ‘portrayal of the tenacity and continuity of humanity amidst […] extreme challenges’ (Patra, 2021: 744) and, as such, center stories of human survival in these new environments. Within video games, we can look to examples such as Horizon Zero Dawn (Guerilla Games, 2017) or Fallout 4 (Bethesda Softworks, 2015), which are post-apocalyptic fictions set outside the geological era of human influence on planet Earth, which is referred to as the post-Anthropocene (Ruffino, 2020; Wallin, 2022). However, it is nonetheless interesting that – despite their placement in the post-Anthropocene – these fictions still rely on the contextual placement of the human experience in these events and settings and often lack a focus on the experience of the natural or non-human in these worlds that largely exist outside the influence of mankind. It is in this area we argue that furry video games can provide insights into this, bridging the gap between the human and the non-human, and providing a key focus on the former through the depiction or experience of the latter.

For this paper, we will examine the popular furry video game series FUGA: Melodies of Steel (CyberConnect2, 2021-2025), in which nature and animals have reclaimed the world in the absence of humankind following an apocalyptic event. In this post-Anthropocene fiction, anthropomorphised canine and feline creatures – the Caninu and Felineko respectively – have become what we could loosely term the “new humanity” on Earth. These races have become dominant in this post-apocalyptic imaginary in a similar, but less antagonistic, fashion to that of mutants or zombies in other fictional post- apocalyptic narratives (Baishya, 2011: 2), actively replacing humanity as the primary influence of the geological era. This isn’t to say that post-apocalyptic fictions such as Fuga or those discussed by Baishya forgo the examination of humanity entirely, but these texts instead focus on the arguable “humanity” of non-human characters in the narrative, as well as providing potential insights into the experience of the non-human in these worlds.

This paper will initially examine the world of Fuga: Melodies of Steel as a post-Anthropocene fictional narrative, bringing in the additional context of the wider narrative that this text is placed within – that of the Little Tail Bronx video game series (CyberConnect2, 1998-Present). Next, we will explore ideas of the reclamation of Earth by nature and animals in a post-Anthropocene environment, especially in relation to nature being symbolic of hope and the promise of building new societies (Pérez-Latorre, et al., 2019: 890) and how this symbolism of reclamation is reflected in the narrative and world of Fuga. Finally, we will discuss the extent to which “humanity” remains represented, reinforced or challenged in these examples of post-apocalyptic fictions through the experiences and behaviours of the Caninu and

Felineko, and how other furry fictional representations in video games can be used as a lens for similar examinations of the human and non-human in these settings and beyond.

Bibliography

Baishya, A.K. 2011. Trauma, Post-Apocalyptic Fiction & The Post-Human, Wide Screen, 3(1).

Bethesda Game Studios. 2015. Fallout 4 [Video game], Bethesda Softworks.

CyberConnect2. 2021. Fuga: Melodies of Steel [Video game], CyberConnect2.

CyberConnect2. 2023. Fuga: Melodies of Steel 2 [Video game], CyberConnect2.

CyberConnect2. 2025. Fuga: Melodies of Steel 3 [Video game], CyberConnect2.

Guerrilla Games. 2017. Horizon: Zero Dawn [Video game], Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Patra, I. 2021. Of surviving humans and apocalyptic machines: Studying the themes of human continuity and posthuman proliferation in the post-apocalyptic world building in Alastair Reynolds’s inhibitor phase, Linguistics and Culture Review, 5(S3), pp. 734-749.

Pérez-Latorre, Ó., Navarro-Remesal, V., Planells de la Maza, A.J., and Sánchez-Serradilla, C. 2019. Recessionary games: Video games and the social imaginary of the Great Recession (2009-2015), Convergence, 25(5-6), pp. 884-900. DOI: 10.1177/1354856517744489.

Ruffino, P. 2020. Nonhuman Games: Playing in the Post-Anthropocene, Death, Culture & Leisure: Playing Dead. Emerald, pp. 11-25. DOI: 10.1108/978-1-83909-037-020201008.

Wallin, J. 2022. Game Preserves: Digital Animals at the Brink of the Post-Anthropocene, Green Letters, 26(1), pp. 102-115. DOI: 10.1080/14688417.2021.2023607.

An Anthology Without an Editor: The Impact of Funny Animals (1972) on the Furry Art Market and Its Valuation

Ian Gray, NYU Tisch School of the Arts

Drawing on Pierre Bourdeau’s theories on the fields of cultural production and distinctiveness, alongside works on creative market status transfer by Organizational Behaviorists like Fabian Accominotti, Ezra Zuckerman, Cecilia Ridgeway, and Joel Podolny, this paper will provide a qualitative examination of (A) status transfer between furry artists, (B) the role of the editor/curator in the furry art market, and (C) the benefits, and limitations, the structure of the furry art marketplaces on the valuation and institutional validation of furry art both inside of and outside of the Furry Fandom.

Finally, this qualitative examination will lay out the groundwork for future quantitative network analysis of and between furry artists showing how status transfer can serve as a tool for the development of a rich and sustainable furry art marketplace.

The one shot anthology Funny Animals (Crumb; 1972) is a seminal work in proto-furry art history. While its influence on the aesthetics of furry art is without doubt, it is the anthology, as a platform and medium for exhibition, that this paper will examine.

Anthologies and group shows, the contemporary norm in furry art, emerge from the constraints and limitations of “Con Culture” in the 1970s and the collectivist zeitgeist of 1960-70s countercultural arts movements. These influences helped shape contemporary furry art, allowing for an explosive output of high quality furry art, driving furry arts’ valuation and market capitalization, all while ultimately contributing to a lack of recognition for furry art outside

of the furry community.

Furry art tends to exist in the context of other furry art. In digital spaces, we frequently see individuals and artists share works by a number of different artists1. In AFK2 spaces, furry artists participate in group art shows, sketchbook swaps, dealers dens and artist alleys, dance competitions, and in the rosters of DJs at raves and parties. Even the humble lobby table and sticker board serve as sites for collective and group exhibition. Multi-artist exhibitions pervade

the furry arts; from fursuit parades to anthology literature.

However, in spite of group exhibitions also being common in the fine arts world, the furry art anthology distinguishes itself by rarely privileging the curator or editor as the fine arts world does. Forwarding collaborative group exhibitions, without a focus on the curator, allows for a higher-than-expected network density in furry art. This encourages artists to engage in resource sharing, raising quality, and provides for a Matthew Effective intra-artist status transfer; high status furry artists can transfer status to low status artists with limited impact on their own positions within the market.

While this transfer benefits furry artists within the furry art market, the opacity of

distinctiveness in status, combined with a lack of recognizable institutional validators (i.e. editors and curators), makes it difficult for those outside of the furry community to engage with furry art, thus hampering furry artists’ ability to participate in both furry the art market and the higher value fine arts market, in spite of forces that suggest this should not only be possible, but likely. (Hahl, Zuckerman, and Kim; 2017)

Footnotes

- It is even common for Artists to share work by other artists on their commercial/consumer facing social media pages.

- AFK stands for ‘Away From the Keyboard’; the term used by Performance Theorist and Black Feminist Theorist Legacy Russell to replace the more common IRL “In Real Life.”

Bibliography

Accominotti, Fabien. “Marché et hiérarchie: La structure sociale des décisions de

production dans un marché culturel.” Histoire & mesure XXIII, no. 2 (December 31,

2008): 177–218. https://doi.org/10.4000/histoiremesure.3703.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1984). Distinction. Routledge. ISBN 0-674-21277-0.

Hahl, Oliver, Ezra W. Zuckerman, and Minjae Kim. “Why Elites Love Authentic Lowbrow Culture: Overcoming High-Status Denigration with Outsider Art.” American Sociological Review 82, no. 4 (August 2017): 828–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417710642.

Reagans, Ray, and Ezra W. Zuckerman. “Networks, Diversity, and Productivity: The Social Capital of Corporate R&D Teams.” Organization Science 12, no. 4 (August 2001): 502–17. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.4.502.10637.

Russell, Legacy. Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. London ; New York: Verso, 2020.

Eurofurence: The Tail of the Travelling Convention

Tim Stoddard

Eurofurence is noteworthy for its size as Europe’s largest furry convention and is the oldest active furry convention in history. It is less known that in its first ten years, it operated as a travelling convention, which would take place at a different venue each year based on submissions by furry community members. There were hopes that Eurofurence would occur in a different European nation each year, like international science fiction conventions.

This study uncovers what happened during those first ten years, using discussions, reports, and testimonies of convention staff members and attendees obtained through archived message boards, conbooks, and announcements. An analysis of this evidence finds that planning a travelling convention comes with unique challenges, such as locating a suitable venue that meets the size and cost requirements in less than a year.

Although there were exceptions, such as Eurofurence 2 (1996) in Sweden and Eurofurence 4 in the Netherlands (1998), the convention would ultimately fall to a core team of EF organisational staff to find and book venues in their home country of Germany. This situation led to divisions in the European furry community, where some protested the consecutive decision to host Eurofurence in Germany.

Some wanted to change the democratic process to root out favouritism, while others simply wanted their home country to host Eurofurence for one year. The key challenges were finding furries who knew best about their own country with the drive to scout and book an eligible venue at an affordable cost and doing so in only a few months.

Having had enough routine debates, the EF organisers made an open call to find a location for Eurofurence 9 (2003). Their call resulted in only one feasible submission: a sports camp in the Czech Republic. Despite promising results and a passionate set of Czech furries to help with organising, the announcement led to a surprising backlash with many German furries dropping out. Eurofurence persevered, resulting in a convention that continues to remain infamous for various logistical issues, but also its charm.

In the end, Eurofurence returned to Germany and decided to stay in a single venue consecutively, building a relationship with the venue’s owner until attendance grew to require a move. Furries who had wished their country to host Eurofurence shifted their focus to hosting conventions of their own, beginning with France in 2003. As of 2025, there are over fifty furry conventions in twenty European countries.

This study is part of a growing body of research into non-American furry communities, which pales compared to the research on American furry fandom. By using this largely untapped source of European furry history, this project will contribute to future research on similar topics.

Fursonas Under Surveillance: Furry Identity, Resistance, and Digital Expression in Iran

Shahriar Khonsari, Freelance Researcher

This presentation explores the emergence and navigation of furry identity within the sociopolitical constraints of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Drawing from digital ethnography, interviews with Iranian and diaspora furries, and content analysis of Persian-language furry platforms (Telegram, Discord, and decentralized art spaces), the paper investigates how the furry community in Iran articulates resistance, queerness, and alternate modes of embodiment under a regime marked by censorship, moral policing, and limited freedom of expression.

While the global furry fandom is often associated with creative freedom and radical self-expression, the stakes are considerably higher in Iran, where non-normative identities and sexualities can carry legal and social repercussions. For Iranian furries—many of whom are also queer, trans, or politically disillusioned—the act of adopting a fursona becomes more than play; it becomes a mechanism of coded communication, spiritual resilience, and radical reimagination. The paper proposes that the Iranian context highlights a critical inflection point in furry studies: how the fandom functions not only as a subculture but also as a survival strategy in authoritarian or theocratic states.

The research is informed by comparative perspectives between Iranian-based creators and those in exile or diaspora, illustrating the bifurcated nature of access, visibility, and safety. In Iran, where anthropomorphism can be misread as religious heresy or Western decadence, furries often conceal their engagement through VPNs, private circles, and anonymous avatars. In contrast, diaspora furries use Persian aesthetics, poetry, and mythology—particularly figures such as Simurgh or shapeshifting jinn—to reclaim cultural heritage through hybrid fursonas that defy both Western and Iranian normative frameworks. This transnational dialogue reflects a form of “diasporic furry worldbuilding,” where global and local identities intersect through layered allegory.

The presentation will also discuss how the Iranian furry community is only indirectly affected by the government’s repressions of the online world. It goes on to illustrate the community’s reaction to this menace, which includes furries’ introduction of encrypted platforms and cultural camouflage as the methods of resistance. The implications are vast: whilst the West may be more and more inclined to demonize the furry phenomenon and even label it as a “threat to childhood” or “fringe deviance”, in Iran, a furry outfit is still a manifestation of a will to get free from the identity’s invisibility through dancing with the reins of darkness.

This presentation, by focusing on the Iranian context—a country that is rarely mentioned in the furry community—opens up the global south of the furry world and brings in ethical issues thus changing the optic on how to approach communities at-risk. The event is designed to address both, academic and community-based audiences, by thus inviting a wide spectrum of interlocutors for a vibrant discussion of the potential and limits of the furry movement as a global site for creative resistance.

Keep Furkeley Weird: A Case Study in Queering the Face of Academia Online

Furries @ Berkeley

Every year, more than 120,000 high school students choose to set their sights on UC Berkeley, but why? Since 1868, Berkeley (“Bezerkeley,” via news pundits) has made a reputation for hippies, geeks, and Silicon Valley changemakers alike. Yet, our applicants face the same hurdle as everyone else in higher education and academia: “You can’t be what you can’t see.” The furry fandom, with its queer history and artistically empowered culture, is a natural antidote. As the largest college furry club in America, we found unprecedented virality reaching out to both furry and non-furry students alike on social media— and hearing what they had to say back. When Furries at Berkeley was formed by our original chairman Carbon in 2022, no one predicted it would blaze a trail totalling several sibling clubs, millions of views, and a highly public stake in the bloody culture war between students and politicians. How does the Furries at Berkeley club make space for aspiring queer academics, and what does the data say about keeping Cal – the most elite public campus in the world – weird?

Furry and Anthropomorphizing Animals as a Response to a Hostile World

Dr. Courtney “Nuka” Plante, Bishop’s University

Duncan Piasecki, University of South Africa

Dr. Janice Moodley, University of South Africa

Dr. Stephen Reysen, East Texas A&M University, Commerce

Dr. Sharon Roberts, Renison University College, University of Waterloo

Dr. Kathleen Gerbasi, State University of New York, Niagara

Humans are a social species: As neither the strongest nor the fastest creature in the wild, we, as a species, thrived through the connections we formed with our fellow humans. So strong is this tribe-like mentality to our survival that we evolved a need to belong to groups (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). When things go according to plan and this need is satisfied, we feel a sense of fulfillment, self-esteem, and happiness. But what do we do when this need goes unsatisfied?

A growing body of literature shows that in addition to being a social species, we humans are a creative breed, with no shortage of creative solutions to our problems. One such solution to the problem of feeling isolated—whether due to bullying and ostracism or simply feeling lonely—is to turn to non- human surrogates. Studies have shown, for example, that being bullied can create difficulties socializing and making friends with other humans (Takizawa et al., 2014) and that lonely people are, instead, more likely to anthropomorphize their technology (Bartz et al., 2016) or their pets (Epley et al., 2008), with anthropomorphized entities being easier to empathize with (Tam et al., 2013) and ultimately identify with (Schultz, 2001).

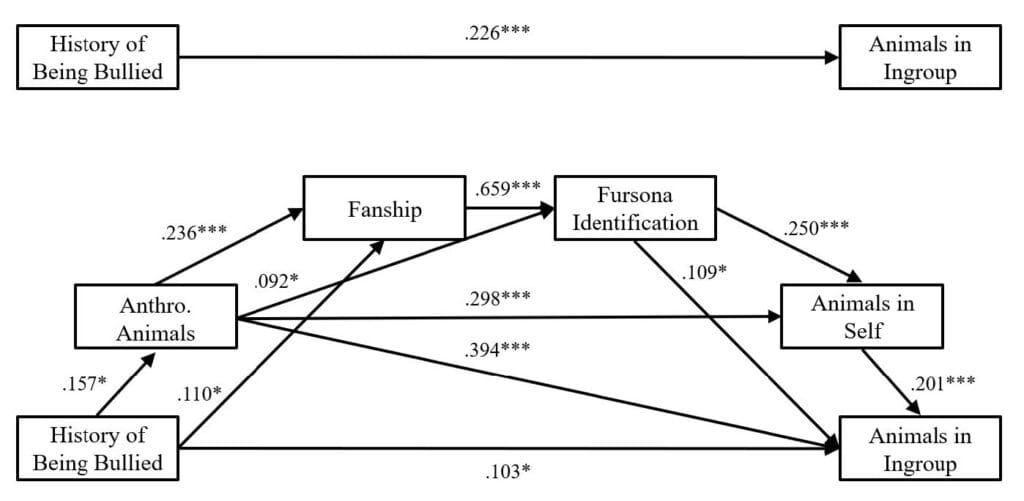

Given that our prior research at Furscience has shown us both that a) furries are a group loosely- defined by its shared interest in anthropomorphizing animals and b) that furries are significantly more likely than the average person to have a history of being bullied (Plante et al., 2023), we proposed a model (see figure below) integrating several existing strands of literature to suggest that those with a history of being bullied may feel a greater sense of connection to non-human animals, in part, because of their increased interest in, and identification with, anthropomorphized animals. We tested variants of this model across a series of furry samples from two different North American furry conventions and from a sample of furries in South Africa. We also tested the generalizability of the model in a non-furry sample of undergraduate students.

Across all four studies we found consistent evidence for our proposed model, suggesting that one way furries specifically—and people more generally—may react to a hostile social world is by turning, instead, to worlds of fantasy non-human characters paradoxically imbued with traits that make them, in many ways, more “human” than those who ostracized them and, thus, easier to identify with. We discuss the implications of these findings, both for existing theoretical research and more practically, such as the mainstream popularity of shows prominently featuring anthropomorphized animal characters in an era of fragmenting social cohesion.

References

Bartz, J. A., Tchalova, K., & Fenerci, C. (2016). Reminders of social connection can attenuate anthropomorphism: A replication and extension of Epley, Akalis, Waytz, and Cacioppo (2008). Psychological Science, 27(12), 1644-1650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616608510

Epley, N., Akalis, S., Waytz, A. & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). Creating social connection through inferential reproduction: Loneliness and perceived agency in gadgets, gods, and greyhounds. Psychological Science, 19(2), 114-120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02056.x

Plante, C. N., Reysen, S., Adams, C., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2023). Furscience! A Decade of Psychological Research on the Furry Fandom. Commerce, TX: International Anthropomorphic Research Project.

Schultz, P. W. (2001). Assessing the structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(4), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0227

Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 777-784. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401

Tam, K.-P., Lee, S.-L., & Chao, M. M. (2013). Saving Mr. Nature: Anthropomorphism enhances connectedness to and protectiveness toward nature. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 49(3), 514-521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.02.001

Brushing Up Against Species: Transgender Feminist Worldbuilding through Fursuit Practices

Alec Esther, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

This presentation considers the feminist worldbuilding potential of the fursuit through the lens of transgender feminism. Fursuits are works of craftsmanship—typically made out of a foam base or resin with fur sewn atop it—designed to approximate the visage of an animal. Fursuits are typically associated with the furry fandom, a subculture of individuals who celebrate anthropomorphic animalism, or the representation of animals adopting human-like traits and forms (á la Disney cartoons). By embodying a trans-species subjectivity that is at once disabling, activating, and often arousing to furry fandom members, fursuits (and furries themselves) debate the merits of seeing species as gender, expanding species positionalities past the “human” and towards a transitive notion of gendered existence. These trans-species embodiments, however, require a critical framework to be politically efficacious. I propose a transgender feminist reading of the fursuit’s shifts in physical embodiment and its culturally established eroticism, which situates trans-species identity within a politic that rejects human supremacy and embodies transgender feminist being. In particular, theories of gender abolition create a practical foundation upon which the species-abolitionist potential of fursuiting rests, demonstrating that supposedly naturalized categories such as “gender” and “species” both are disposable and capable of radical revolutionization. Aligning fursuiting practices with specifically transgender feminist principles identifies individual moments of embodied species performance and erotic experience as epistemically and socially transformative, emphasizing the need for further analysis of moments of furry intimacy and physical fursuited contact.

To augment the arguments herein, this presentation is planned to be facilitated in fursuit.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bey, Marquis. 2022. Cistem Failure: Essays on Blackness and Cisgender. ASTERISK: Gender, Trans-, and All That Comes After. Durham: Duke University Press.

Chu, Andrea Long. 2017. “On Liking Women.” N+1 (blog). November 29, 2017.

https://www.nplusonemag.com/issue-30/essays/on-liking-women/.

Colebrook, Claire. 2015. “What Is It Like to Be a Human?” TSQ: Transgender Studies

Quarterly 2 (2): 227–43. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2867472.

Trans-Species Panic: the Furry Slope of Anti-Trans Legislation

Alexander Rudenshiold, University of California, Irvine

Caro Mooney, University of California, Irvine

It seems unlikely that ‘furries’ would occur, or reoccur, specifically in any legislative proposal. Yet, since 2021, there has been a flurry of right-wing bills in the United States which have in one way or another sought to eliminate furries—members of the anthropomorphic animal-centered queer “furry” subculture—from public spaces, primarily schools. These bills function as part of a broader attempt to codify the ostracization of LGBTQ youth and, more directly, to criminalize the affirmation of transgender identity expression in public education. Building from homophobic ‘grooming’ tropes and absurd, widespread hoax media which claims that schools have introduced litter boxes to affirm children’s alleged ‘furry’ trans-species identities, right-wing legislators have sought increasingly to expand anti-transgender (anti-trans) regulations, using their absurd depiction of ‘furries’ as justification. In this article, we historicize this anti-furry and anti- trans legislative movement, and provide a framework for understanding it through queer criminology, media studies, and moral panic literature. We argue that right-wing activists’ and legislators’ representation of furry subculture as trans-species—and thus, to their minds, at the bottom of an absurd, unnatural, and perverse slippery slope—operates as a proxy through which transgender identities can be similarly attacked. This ongoing anti- furry legislative wave, we find, exemplifies a deepening relationship between moral panic media and (particularly anti-trans) right-wing legislation which requires urgent attention from scholars across criminology and media studies.

Sparklefurs: Virtual Avatars, Physical Embodiment, and Intergenerational Histories in the Furry Fandom

Belle Walston, University of Texas at Austin

Mark Zubrovich (b. 1992) is a painter and textile artist whose recent work centers on what he calls “the furry rite of passage”: developing his fursona, a cobalt blue mutt named Bruce.1 Zubrovich creates images of his fursona to “process and experience emotion” to the extreme, exaggerating his own perceptions of the world.2 He often refers to these paintings of Bruce as self-portraits, many of which depict the character cartoonishly acting out Zubrovich’s sensations, such as carving his nose, feet, and hip with a knife to signify Zubrovich’s loss of smell after COVID-19 and the onset of his chronic pain condition. Bruce’s body is one that can only exist in fantasy, but by imagining Bruce as himself, Zubrovich pushes beyond the perceived boundaries of his own ontology.

This paper considers Zubrovich’s depictions of Bruce as the artist’s own embodiments of a sparkledog—an avatar derived from digital art subcultures of the late 2000s, initially characterized by fantastical powers and queer-coded fashion. Although optimism about the internet’s liberatory potential declined after the burst of the dot-com bubble, the furry fandom has continued to view computer-mediated communication as a space for identity exploration beyond the limits of the physical body. I situate Zubrovich’s practice within the historical context of the internet’s widespread adoption, drawing on intergenerational dialogues within the furry fandom and scholarly discourse on cyber-utopianism. By identifying Zubrovich and other furry artists as creators of historically and affectively engaged works featuring sparklefurs, I argue for their significance within visual traditions concerned with nonhuman embodiment and the expression of queer desire.

Endnotes

- Zubrovich, “Info.”

- Zubrovich, “Interview with Mark Zubrovich,” by Clare Gemima.

Chasing Our Tails: (Trans)Species Critique and Coalitional Politics

Juniper Clark, University of Pennsylvania

This paper offers one particular avenue that future work in furry studies might take, drawing on methodological and theoretical considerations from critical animal and multispecies studies that highlight the radical potentialities of nonhuman community work and the political alliances they might engender. While care and concern for the well-being of other animals is shared amongst a sizeable portion of the fandom and its subcultural neighbors (therian, otherkin, etc.), understandings of animality (what many in animal studies refer to as the figure of “the animal”) and its implications within broader networks of power are relatively under-theorized. Positioning furry next to the wide array of human activity that implicates other animals, I argue that it is generative to think of fandom practices as instances of what Una Chaudhuri has called zooësis, or “the discourse and representation of species in contemporary culture and performance” that “consists of the myriad performance and semiotic elements involved in and around the vast field of cultural animal practices” (Chaudhuri 2003). If recourse to animality often operates as a strategy of survival (Massumi 2014)—in the sense that to play (as) the nonhuman is to play in spite of the (human) body and its existential baggage—where might we begin to locate “living” animals (and not simply species essentializations) in performances of and identifications with “animality?” Beyond one-dimensional critiques that simply reduce nonhuman identity formation and performances of animality to something like “animal drag” (a comparison we might nonetheless engage with in its own right), I wonder after a configuration of furriness/therianism that takes seriously the proverbial debts (aesthetic, cultural, political, material-semiotic, or otherwise) such communities owe to their nonhuman kin.

Additionally, against claims that the adoption of nonhuman identity is simply a retreat from the pressures of the mundane, I am interested in thinking through the ways in which participation in such communities functions as both a liberatory site of coalition-building with other political struggles (particularly with other marginalized populations that must contend with hegemonic processes of animalization/dehumanization) as well as a point of critical departure for resisting dominant “rhetorics of animality” (Baker 1993) that have become normalized under anthropocentric hegemony. If historical formulations of the minoritized human (and animal) subject have tended to characterize such bodies as variously in/non/sub-human to violent, exclusionary ends, how might we forge alliances across species lines, and in opposition to narrow conceptions of subjecthood that often exclude other forms of life? Moreover, how might we place such concerns in generative dialogue with decolonial approaches and more-than-human theorizing that reject liberal humanism’s overdetermination of “the human” to the colonial/Eurocentric genre of “Man” (Wynter 2003)?

References

Baker, Steve. 1993. Picturing the Beast: Animals, Identity, and Representation. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

Chaudhuri, Una. 2003. “Animal Geographies: Zooesis and the Space of Modern Drama.” Modern Drama 46 (4): 646-662.

Massumi, Brian. 2014. What Animals Teach Us about Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Wynter, Sylvia. 2003. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument.” The New Centennial Review 3 (3): 257-337.